After five years in Berlin and almost three years writing about the city, it’s time for me to publish about the Berlin Wall, a wall that defined the city for almost thirty years and whose traces are still visible more than three decades after its fall and almost total destruction.

I propose to focus here on the section of the Wall at Bernauer Strasse, in the north of the city, a place that gives an idea of what the Wall was: a system made up of different infrastructures that made it an almost impassable frontier.

In 1945, the four Allied nations – the USA, the USSR, the United Kingdom and France – divided Germany into four zones of occupation, with Berlin itself divided between the four victors. Very quickly, the allies of the war became enemies and this was particularly evident in Berlin, where the Soviets and then the GDR regime tried to get the Western allies to leave in order to reclaim the city. In 1948 the Soviets set up a complete blockade of the city, which failed and reinforced West Berlin’s attachment to the Western world.

One of the emblematic sites of the blockade was Tempelhof airport, which you can visit today and about which I wrote a post: Berlin Tempelhof – an airport in the city center

Between 1949, when the two states were created, and 1961, the East German regime witnessed a huge wave of departures. On average, more than 200,000 East Germans fled to the West every year, most of them via Berlin, where the border was difficult to guard. The country has a population of 18 million, and half of those leaving are young people under the age of 25. This was a worrying situation for the regime and Walter Ulbricht decided to close the border with a wall, although he would have to convince his Soviet allies to do so.

The preparations were meticulous, the secret very well kept and on the night of 13 August 1961 the first physical separation was put in place: barbed wire, cinder blocks, etc. with 10,000 armed guards. The task was a huge one: the wall was 168km long, 43km of which was between the two parts of the city, with the rest separating West Berlin from Brandenburg.

Over time, these first elements of the wall were reinforced and replaced, until the last model was built in 1975: concrete modules 3.6 metres high, crowned by a rounded element that made it even more difficult to cross. It is this version, the fourth generation of the wall, that has survived inside the city.

What’s special about Bernauer Strasse is that the border leaves the pavement and the street to the west, while the buildings are to the east. In the first few hours, the inhabitants jumped out of the windows before they were walled up and the buildings razed to the ground to make way for the outer wall, the area in between and the inner wall. Today, this area has been preserved, a large lawn has replaced the death zone, and the outer wall is intact in places, or has been rebuilt with iron pillars.

There was a church in this area, which was eventually destroyed by the GDR, and a memorial chapel was rebuilt on its site.

There are also watchtowers in the area between the two walls, and there is still one at Bernauer Strasse, somewhat hidden from the street, surrounded by an empty space that can be glimpsed through the cracks in the surrounding wall.

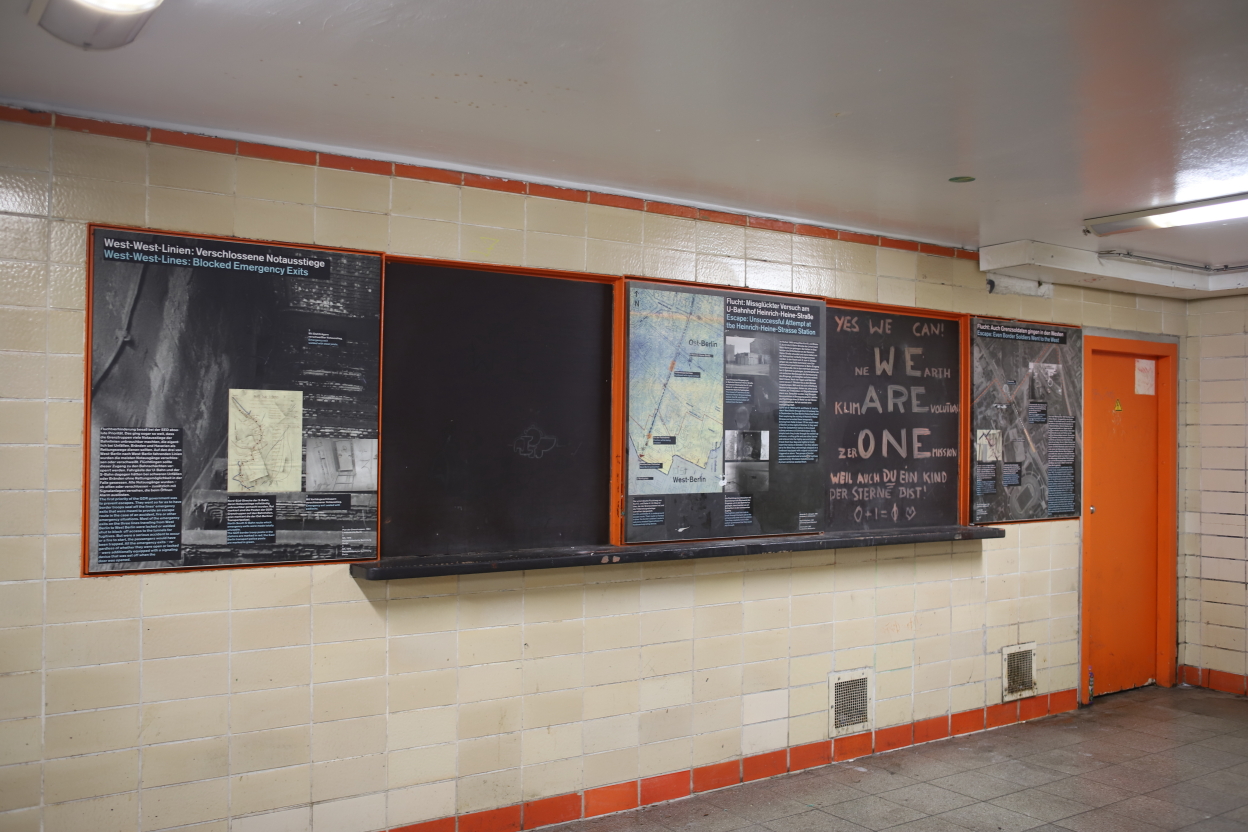

But it’s not enough to build a wall to make the border watertight (or almost watertight), we also have to block the underpasses and make sure that the transport system (UBahn, SBahn) doesn’t allow people to leave East Berlin. As a result, some stations will be closed, with trains no longer stopping there. This is the case of NordBahnhof, which has been rebuilt and reopened since the fall of the Wall, of course.

Part of it has been preserved and is now used as a small exhibition room.

From the end of 1989 and the fall of the Wall, a controversy arose: should it be completely destroyed or preserved?

The reality was that whole sections of it quickly disappeared, and parts of it can be found all over the world. Real estate pressure will also rapidly lead to the reconstruction of the very important areas that made up the death zone. The best example of this is Potsdamer Platz, which was the largest building site in Europe in the early 2000s.

In the end, a few fragments were preserved, including the one at Bernauer Strasse, which gives a good idea of the width of the system. The entire length of the wall has been marked on the ground, enabling the route to be followed despite all the urban transformations.

Where to find this street: https://maps.app.goo.gl/9jufoS6GUwMmPsDE8

If you’re particularly interested in this period of Berlin’s history, I suggest you take a look at my post on the prison run by the Stasi, the GDR’s secret police: Why visiting the former Stasi jail in Berlin?

I also recommend a post on Check Point Bravo, the exit point from West Berlin by car: Berlin Check point Bravo.